Carrying capacity is the number of organisms that an ecosystem can sustainably support. An ecosystem’s carrying capacity for a particular species may be influenced by many factors, such as the ability to regenerate the food, water, atmosphere, or other necessities that populations need to survive.

In biology, the concept of carrying capacity relates the number of organisms which can survive to the resources within an ecosystem. Ecosystems cannot exceed their carrying capacity for a long period of time. In situations where the population density of a given species exceeds the ecosystem’s carrying capacity, the species will deplete its source of food, water, or other necessities. Soon, the population will begin dying off. A population can only grow until it reaches the carrying capacity of the environment. At that point, resources will not be sufficient to allow it to continue to grow over the long-term.

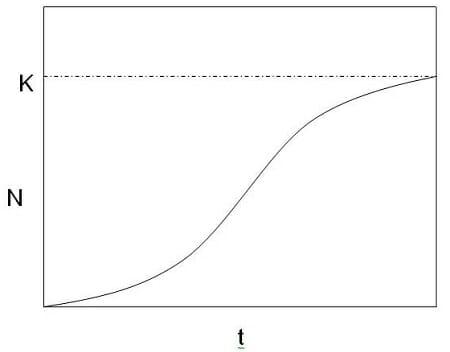

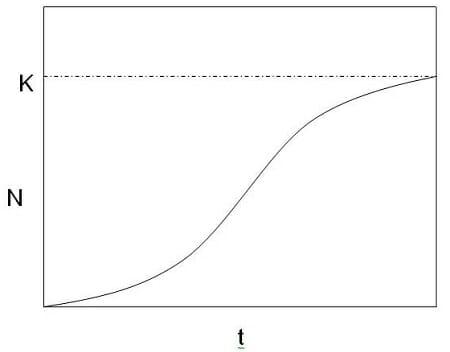

The graph above shows the population (N) of a certain species over time (t). At the carrying capacity (K), the population stops growing as resources are maxed out.

An example of a situation in which the carrying capacity of an environment was exceeded can be seen within the deer populations of North America.

After the widespread elimination of wolves – the natural predator of North American deer – the deer reproduced until their need for food exceeded the environment’s ability to regenerate their food. In many areas, this resulted in large numbers of deer starving until the deer population was severely reduced.

Before Europeans colonized North America, one of its main forest herbivores were deer. Ordinarily existing in small groups, populations of deer were kept in check by wolves, the top predator of these forest ecosystems.

Deer, being a fairly large North American herbivore, were capable of eating leaves off of trees and shrubs, as well as low-growing plants like flowers and grass. And they required a lot of leaves to keep them going, as members of different species of deer could weigh anywhere from 50 to 1,500 pounds!

But when European settlers severely depleted the population of wolves, who they found to be a danger to human children and livestock, an unexpected consequence resulted: deer began to multiply out of control, until they exceeded the carrying capacity of their environment.

As a result, deer began to starve. Plants species also began to suffer, some even being threatened with extinction as the starving deer ate all the green plants they could find.

When humans realized what was happening – and it began to affect their own food sources, after wild deer began to invade gardens and farms looking for crops to eat – they began to give nature a helping hand in reducing the deer population.

In modern times, some areas “cull” deer – a practice where deer are systematically hunted, not just for meat or sport, but to prevent deer starvation and damage to plants. Other areas have even begun to re-introduce wolves, and these areas have seen healthier ecosystems, gardens, and crops as a result.

The story of the North American wolves and deer has acted as a cautionary tale for people considering making changes of any kind to their natural environment, which might have unintended consequences.

The hypothetical “Daisyworld” model is a model developed by scientists to study how organisms change their environment, and how ecosystems self-regulate.

In the original “Daisyworld” mathematical simulation, there were only two types of life forms: black daisies, which increase the environment’s temperature by absorbing heat from the Sun (this is a real property of black materials), and white daisies, which decrease the environment’s temperature by reflecting the Sun’s heat (this is also a real effect of white-colored materials).

Each species of daisies had to live in a proper balance with the other species. If the white daisies overpopulated, the world would become too cold. Daisies of both types would begin to die off, and the world would start to regain equilibrium. The same held true for black daisies: if they become overpopulated, the world becomes warmer and warmer until the daisies began to die off again.

Real-life ecosystems are much more complicated than this, of course.

Each organism has many needs, and how well the environment can meet those needs might depend on what other organisms it shares the environment with.

Humans have become one of the world’s only global species my mastering technology. Time and time again, the human species has overcome a factor, such as availability of food or the presence of natural predators, that limited our population.

The first major human population explosion happened after the invention of agriculture, in which humans learned that we could grow large numbers of our most nutritious food plants by saving seeds to plant in the ground. By making sure those seeds got enough water and were protected from competition from weeds and from being eaten by other animals we insured a steady food supply.

When agriculture was invented, the human population skyrocketed – scientists think that without agriculture, between 1 million and 15 million humans were able to live on Earth. Today, there are about 1 million humans in the city of Chicago alone!

By the Middle Ages, when well-organized agriculture had emerged on every continent, there were about 450 million – or about half a billion – humans on earth.

A new revolution in Earth’s capacity to carry humans began in the 18th and 19th centuries when humans began to apply advanced and automated technology to agriculture. The use of inventions such as the mechanical corn picker and crop rotation – a way of growing different crops in a sequence that enriches the soil and leads to higher yields – allowed humans to produce even more food. As a result, the world population tripled from about half a billion to 1.5 billion people.

In the twentieth century, a third revolution occurred when humans began to learn how to rewrite the genomes of the plants, using viruses to insert new genes into seeds directly instead of relying on selective breeding and random mutation to increase crop yields. The result was another drastic increase in the Earth’s ability to produce food for humans.

During the 20th century, Earth’s human population more than quadrupled, from 1.5 billion to 6.1 billion. We’ve come a long way from the pre-agricultural days!

But some scientists worry that we may be well on our way to exceeding the Earth’s carrying capacity – or that we may have already done so.

Though we have massively expanded the carrying capacity for the human species, our activities are not without consequence. There are several possible limitations on the human species that not even technology can save us from.

Scientists point to the rapid decline of bee populations – which are necessary to pollinate some of our crops, and which many scientists believe are being killed by pesticides we use to protect those same crops – as evidence that our current food production practices may not be sustainable for much longer.

The proliferation of poisonous algae, which can poison our water supplies and which feeds on the same fertilizer we use to feed our crops, is another worrisome sign that we may be exceeding our carrying capacity, and may begin to cause problems for ourselves if our population continues to grow.

Some scientists fear that humans may exceed the Earth’s carrying capacity for humans, and encourage the use of contraception to decrease birth rates in order to prevent human populations from exhausting their sources of food and other vital resources.