There are over two million farms in the United States, and more than half the nation’s land is used for agricultural production. 1 The number of farms has been slowly declining since the 1930s, 2 though the average farm size has remained about the same since the early 1970s. 3 Agriculture also extends beyond farms. It includes industries such as food service and food manufacturing.

Did You Know?

Agriculture is very sensitive to weather and climate. 4 It also relies heavily on land, water, and other natural resources that climate affects. 5 While climate changes (such as in temperature, precipitation, and frost timing) could lengthen the growing season or allow different crops to be grown in some regions, 6 it will also make agricultural practices more difficult in others.

The effects of climate change on agriculture will depend on the rate and severity of the change, as well as the degree to which farmers and ranchers can adapt. 7 U.S. agriculture already has many practices in place to adapt to a changing climate, including crop rotation and integrated pest management. A good deal of research is also under way to help prepare for a changing climate.

Learn more about climate change and agriculture:

Climate change can affect crops, livestock, soil and water resources, rural communities, and agricultural workers. However, the agriculture sector also emits greenhouse gases into the atmosphere that contribute to climate change.

Read more about greenhouse gas emissions on the Basics of Climate Change page.

Learn how the agriculture sector is reducing methane emissions from livestock waste through the AgSTAR program. For a more technical look at emissions from the agriculture sector, take a look at EPA's Greenhouse Gas Emissions Inventory chapter on agriculture activities in the United States.

Climate change may affect agriculture at both local and regional scales. Key impacts are described in this section.

Climate change can make conditions better or worse for growing crops in different regions. For example, changes in temperature, rainfall, and frost-free days are leading to longer growing seasons in almost every state. 8 A longer growing season can have both positive and negative impacts for raising food. Some farmers may be able to plant longer-maturing crops or more crop cycles altogether, while others may need to provide more irrigation over a longer, hotter growing season. Air pollution may also damage crops, plants, and forests. 9 For example, when plants absorb large amounts of ground-level ozone, they experience reduced photosynthesis, slower growth, and higher sensitivity to diseases. 10

Climate change can also increase the threat of wildfires. Wildfires pose major risks to farmlands, grasslands, and rangelands. 11 Temperature and precipitation changes will also very likely expand the occurrence and range of insects, weeds, and diseases. 12 This could lead to a greater need for weed and pest control. 13

Pollination is vital to more than 100 crops grown in the United States. 14 Warmer temperatures and changing precipitation can affect when plants bloom and when pollinators, such as bees and butterflies, come out. 15 If mismatches occur between when plants flower and when pollinators emerge, pollination could decrease. 16

Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of heavy precipitation in the United States, which can harm crops by eroding soil and depleting soil nutrients. 18 Heavy rains can also increase agricultural runoff into oceans, lakes, and streams. 19 This runoff can harm water quality.

When coupled with warming water temperatures brought on by climate change, runoff can lead to depleted oxygen levels in water bodies. This is known as hypoxia. Hypoxia can kill fish and shellfish. It can also affect their ability to find food and habitat, which in turn could harm the coastal societies and economies that depend on those ecosystems. 20

Sea level rise and storms also pose threats to coastal agricultural communities. These threats include erosion, agricultural land losses, and saltwater intrusion, which can contaminate water supplies. 21 Climate change is expected to worsen these threats. 22

Agricultural workers face several climate-related health risks. These include exposures to heat and other extreme weather, more pesticide exposure due to expanded pest presence, disease-carrying pests like mosquitos and ticks, and degraded air quality. 23 Language barriers, lack of health care access, and other factors can compound these risks. 24 Heat and humidity can also affect the health and productivity of animals raised for meat, milk, and eggs. 25

For more specific examples of climate change impacts in your region, please see the National Climate Assessment.

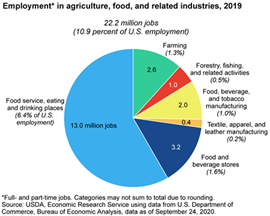

Agriculture contributed more than $1.1 trillion to the U.S. gross domestic product in 2019. 26 The sector accounts for 10.9 percent of total U.S. employment—more than 22 million jobs. 27 These include not only on-farm jobs, but also jobs in food service and other related industries. Food service makes up the largest share of these jobs at 13 million. 28

Cattle, corn, dairy products, and soybeans are the top income-producing commodities. 29 The United States is also a key exporter of soybeans, other plant products, tree nuts, animal feeds, beef, and veal. 30

Many hired crop farmworkers are foreign-born people from Mexico and Central America. 31 Most hired crop farmworkers are not migrant workers; instead, they work at a single location within 75 miles of their homes. 32 Many hired farmworkers can be more at risk of climate health threats due to social factors, such as language barriers and health care access.

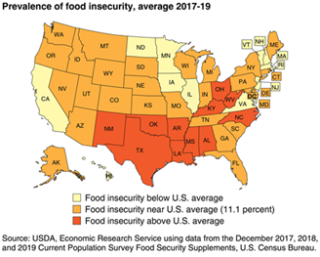

Climate change could affect food security for some households in the country. Most U.S. households are currently food secure. This means that all people in the household have enough food to live active, healthy lives. 33 However, 13.8 million U.S. households (about one-tenth of all U.S. households) were food insecure at least part of the time in 2020. 34 U.S. households with above-average food insecurity include those with an income below the poverty threshold, those headed by a single woman, and those with Black or Hispanic owners and lessees. 35

Climate change can also affect food security for some Indigenous peoples in Hawai'i and other U.S.-affiliated Pacific islands. Climate impacts like sea level rise and more intense storms can affect the production of crops like taro, breadfruit, and mango. 36 These crops are often key sources of nutrition and may also have cultural and economic importance.

We can reduce the impact of climate change on agriculture in many ways, including the following:

See additional actions you can take, as well as steps that companies can take, on EPA’s What You Can Do About Climate Change page.

Learn more about some of the key indicators of climate change related to this sector from EPA’s Climate Change Indicators:

4 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture. USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 1.

5 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 393.

6 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture. USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 22.

7 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 393.

8 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 401.

9 Nolte, C.G., et al. (2018). Ch. 13: Air quality. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 513.

11 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 401.

12 Ziska, L., et al. (2016). Ch. 7: Food safety, nutrition, and distribution. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 197.

13 Ziska, L., et al. (2016). Ch. 7: Food safety, nutrition, and distribution. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 197.

15 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture. USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 20.

16 Walsh, M.K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture. USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 40.

17 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 405.

18 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 409.

19 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 409.

20 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 405.

21 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 405.

22 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 405.

23 Gamble, J.L., et al. (2016). Ch. 9: Populations of concern. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, pp. 247–286.

25 Walsh, M. K., et al. (2020). Climate indicators for agriculture. USDA Technical Bulletin 1953. Washington, DC, p. 20.

36 Keener, V., et al. (2018). Ch. 27: Hawai‘i and U.S.-affiliated Pacific islands. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 1269.

37 Mankin, J.S., et al. (2021). NOAA Drought Task Force report on the 2020–2021 southwestern U.S. drought. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Drought Task Force; NOAA Modeling, Analysis, Predictions and Projections Programs; and National Integrated Drought Information System, p 4.

38 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 401.

39 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 409.

40 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 407.

41 Gowda, P., et al. (2018). Ch. 10: Agriculture and rural communities. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 415.